A Patient's Guide to Lumbar Spondylolisthesis

Introduction

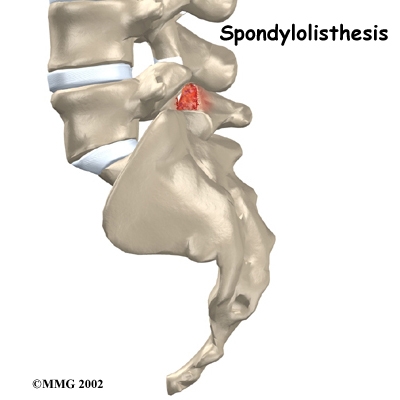

Normally, the bones of the spine (the vertebrae) stand neatly stacked on top of one another. Ligaments and joints support the spine. Spondylolisthesis alters the alignment of the spine. In this condition, one of the spine bones slips forward over the one below it. As the bone slips forward, the nearby tissues and nerves may become irritated and painful.

This guide will help you understand

- how the problem develops

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts of the spine are involved?

The human spine is made up of twenty-four spinal bones, called vertebrae. Vertebrae are stacked on top of one another to create the spinal column. The spinal column gives the body its form. It is the body's main upright support. The section of the spine in the lower back is called the lumbar spine.

The lumbar spine is made of the lower five vertebrae. Doctors often refer to these vertebrae as L1 to L5. These five vertebrae line up to give the low back a slight inward curve. The lowest vertebra of the lumbar spine, L5, connects to the top of the sacrum, a triangular shaped bone at the base of the spine that fits between the two pelvic bones.

Each vertebra is formed by a round block of bone, called a vertebral body. A circle of bone attaches to the back of the vertebra. When the vertebrae are stacked on top of each other, these bony rings create a hollow tube. This tube, called the spinal canal, surrounds the spinal cord as it passes through the spine. Just as the skull protects the brain, the bones of the spinal column protect the spinal cord.

The spinal cord only extends to about L2. Below this level, the canal encloses a bundle of nerves that goes to the lower limbs and pelvic organs. The Latin term for this bundle of nerves is cauda equina, meaning "horse's tail."

Two sets of bones form the spinal canal's bony ring. Two pedicle bones attach to the back of each vertebral body. Two lamina bones complete the ring. The place where the lamina and pedicle bones meet is called the pars interarticularis, or "pars" for short. There are two such meeting points on the back of each vertebra, one on the left and one on the right. The pars is thought to be the weakest part of the bony ring.

Intervertebral discs separate the vertebral bodies. The discs normally work like shock absorbers. They protect the spine against the daily pull of gravity. They also protect the spine during strenuous activities that put strong force on the spine, such as jumping, running, and lifting.

The lumbar spine is supported by ligaments and muscles. The ligaments, which connect bones together, are arranged in layers and run in multiple directions. Thick ligaments connect the bones of the lumbar spine to the sacrum (the bone below L5) and pelvis.

Between the vertebrae of each spinal segment are two facet joints. The facet joints are located on the back of the spinal column. There are two facet joints between each pair of vertebrae--one on each side of the spine. A facet joint is made of small, bony knobs that line up along the back of the spine. Where these knobs meet, they form a joint that connects the two vertebrae. The alignment of the facet joints of the lumbar spine allows freedom of movement as you bend forward and back.

The anatomy of the lumbar spine is often discussed in terms of spinal segments. Each spinal segment includes two vertebrae separated by an intervertebral disc, the nerves that leave the spinal cord at that level, and the facet joints that link each level of the spinal column.

Causes

Why do I have this problem?

In younger patients (under twenty years old), spondylolisthesis usually involves slippage of the fifth lumbar vertebra over the top of the sacrum. There are several reasons for this. First, the connection of L5 and the sacrum forms an angle that is tilted slightly forward, mainly because the top of the sacrum slopes forward. Second, the slight inward curve of the lumbar spine creates an additional forward tilt where L5 meets the sacrum. Finally, gravity attempts to pull L5 in a forward direction.

Facet joints are small joints that connect the back of the spine together. Normally, the facet joints connecting L5 to the sacrum create a solid buttress to prevent L5 from slipping over the top of the sacrum. However, when problems exist in the disc, facet joints, or bony ring of L5, the buttress becomes ineffective. As a result, the L5 vertebra can slip forward over the top of the sacrum.

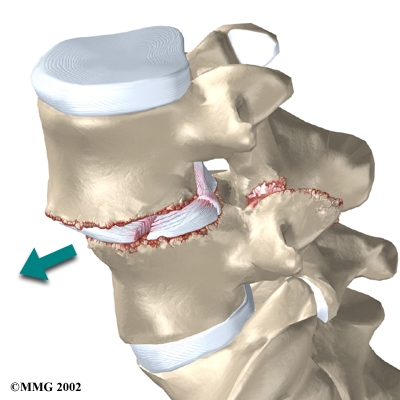

A condition called spondylolysis can also cause the slippage that happens with spondylolisthesis. Spondylolysis is a defect in the bony ring of the spinal column. It affects the pars interarticularis, mentioned above. This defect is most commonly thought to be a "stress fracture" that happens from repeated strains on the bony ring. Participants in gymnastics and football commonly suffer these strains. Spondylolysis can lead to the spine slippage of spondylolisthesis when a fracture occurs on both sides of the bony ring. The back section of the bony ring separates from the main vertebral body, so the injured vertebra is no longer connected by bone to the one below it. In this situation, the facet joints can't provide their normal support. The vertebra on top is then free to slip forward over the one below.

A traumatic fracture in the bony ring can lead to slippage when the fracture goes completely through both sides of the bony ring. The facet joints are no longer able to provide a buttress, allowing the vertebra with the crack in it to slip forward. This is similar to what happens when spondylolysis (mentioned earlier) occurs on both sides of the bony ring, but in this case it happens all at once.

Degenerative changes in the spine (those from wear and tear) can also lead to spondylolisthesis. The spine ages and wears over time, much like hair turns gray. These changes affect the structures that normally support healthy spine alignment. Degeneration in the disc and facet joints of a spinal segment causes the vertebrae to move more than they should. The segment becomes loose, and the added movement takes a additional toll on the structures of the spine. The disc weakens, pressing the facet joints together. Eventually, the support from the facet joints becomes ineffective, and the top vertebra slides forward. Spondylolisthesis from degeneration usually affects people over 40 years old. It mainly involves slippage of L4 over L5.

Symptoms

What does the condition feel like?

An ache in the low back and buttock areas is the most common complaint in patients with spondylolisthesis. Pain is usually worse when bending backward and may be eased by bending the spine forward.

Spasm is also common in the low back muscles. The hamstring muscles on the back of the thighs may become tight.

The pain can be from mechanical causes. Mechanical pain is caused by wear and tear on the parts of the spine. When the vertebra slips forward, it puts a painful strain on the disc and facet joints.

Slippage can also cause nerve compression. Nerve compression is a result of pressure on a nerve. As the spine slips forward, the nerves may be squeezed where they exit the spine. This condition also reduces space in the spinal canal where the vertebra has slipped. This can put extra pressure on the nerve tissues inside the canal. Nerve compression can cause symptoms where the nerve travels and may include numbness, tingling, slowed reflexes, and muscle weakness in the lower body.

Nerve pressure on the cauda equina, the bundle of nerve roots within the lumbar spinal canal, can affect the nerves that go to the bladder and rectum. The pressure may cause low back pain, pain running down the back of both legs, and numbness or tingling between the legs in the area you would contact if you were seated on a saddle.

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose the problem?

Diagnosis begins with a complete history and physical exam. Your doctor will ask questions about your symptoms and how your problem is affecting your daily activities. Your doctor will also want to know what positions or activities make your symptoms worse or better.

Next the doctor examines you by checking your posture and the amount of movement in your low back. Your doctor checks to see which back movements cause pain or other symptoms. Your skin sensation, muscle strength, and reflexes are also tested.

Doctors will usually order X-rays of the low back. The X-rays are taken with your spine in various positions. They can be used to see which vertebra is slipping and how far it has slipped.

If more information is needed, your doctor may order computed tomography (a CT scan). This is a detailed X-ray that lets the doctor see "slices" of the body's tissue. If you have nerve problems, the doctor may combine the CT scan with myelography. To do this, a special dye is injected into the space around the spinal canal--the subarachnoid space. During the CT scan, the dye highlights the spinal nerves. The dye can improve the accuracy of a standard CT scan for diagnosing the health of the nerves.

Your doctor may also order an MRI scan (magnetic resonance imaging scan). The MRI machine uses magnetic waves rather than X-rays to show the soft tissues of the body. It can help in the diagnosis of spondylolisthesis. It can also provide information about the health of nerves and other soft tissues.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

When the vertebra hasn't slipped very far, doctors begin by prescribing nonsurgical treatments. In some cases, the patient's condition is simply monitored to see if symptoms improve.

Your doctor may ask that you rest your back by limiting your activities. This is to help decrease inflammation and calm muscle spasm. You may need to take time away from sports or other strenuous activities to give your back a chance to heal.

If you still have symptoms after a period of rest, your doctor may have you wear a rigid back brace or cast for two to three months. Keeping the spine from moving can help ease pain and inflammation.

Patients often work with a physical therapist. After evaluating your condition, your therapist can assign positions and exercises to ease your symptoms. Your therapist can design an exercise program to improve flexibility in your low back and hamstrings and to strengthen your back and abdominal muscles.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect as I recover?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Nonsurgical treatment for spondylolisthesis commonly involves physical therapy. Your doctor may recommend that you work with a physical therapist a few times each week for four to six weeks. In some cases, patients may need a few additional weeks of care.

The first goal of treatment is to control symptoms. Your therapist works with you to find positions and movements that ease pain. Treatments of heat, cold, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation may be used to calm pain and muscle spasm. Patients are shown how to stretch tight muscles, especially the hamstring muscles on the back of the thigh.

As patients recover, they gradually advance in a series of strengthening exercises for the abdominal and low back muscles. Working these "core" muscles helps patients move easier and lessens the chances of future pain and problems.

A primary purpose of therapy is to help you learn how to take care of your symptoms and prevent future problems. You'll be given a home program of exercises to continue improving flexibility, posture, endurance, and low back and abdominal strength. The therapist will also describe strategies you can use if your symptoms flare up.

All content provided by eORTHOPOD® is a registered trademark of Medical Multimedia Group, L.L.C.. Content is the sole property of Medical Multimedia Group, L.L.C.. and used herein by permission.

All materials from eORTHOPOD® are the sole property of Medical Multimedia Group, L.L.C.. and are used herein by permission. eORTHOPOD® is a registered trademark of Medical Multimedia Group, L.L.C..

|